Britain’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is facing scrutiny after a senior official admitted that a cache of documents on Keenie Meenie Services (KMS) – a British mercenary firm accused of war crimes in Sri Lanka – was inexplicably withheld for years despite being cleared for release.

In an information tribunal hearing in London earlier this month, FCDO chief censor Graham Hand testified that it was “very complicated, a little bit mysterious and regrettable” that the files remained hidden long after they were supposed to be made public. The unexplained delay – nearly six years – meant that key evidence about British involvement in Sri Lanka’s civil conflict was only disclosed in February 2025, on the eve of the tribunal.

The tribunal, brought by investigative outlet Declassified UK, focused on why the Foreign Office had failed to release documents related to KMS. Freedom of Information requests for these files were first lodged in 2018 during research for a book and documentary on the mercenary company. While some papers were released over the years and others formally withheld under exemptions, this particular tranche was neither released nor officially exempted – it was simply not handed over to the requesters.

Hand, a former ambassador who leads the FCDO’s team of sensitivity reviewers, could not clarify exactly when the documents had originally been approved for release or why they had been withheld for so long. He conceded under cross-examination that the situation was highly irregular, calling it “mysterious”.

The withheld files, finally disclosed in February 2025, date back to April 1985 – the period of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s visit to Sri Lanka. The tribunal heard that these papers had in fact been cleared for release years ago, under standard 30-year declassification rules, yet remained buried in Foreign Office archives without explanation. Government lawyers at the hearing offered no satisfactory reason for the oversight. The judge is expected to issue a ruling on the case at a later date, which may determine whether further KMS records should be made public.

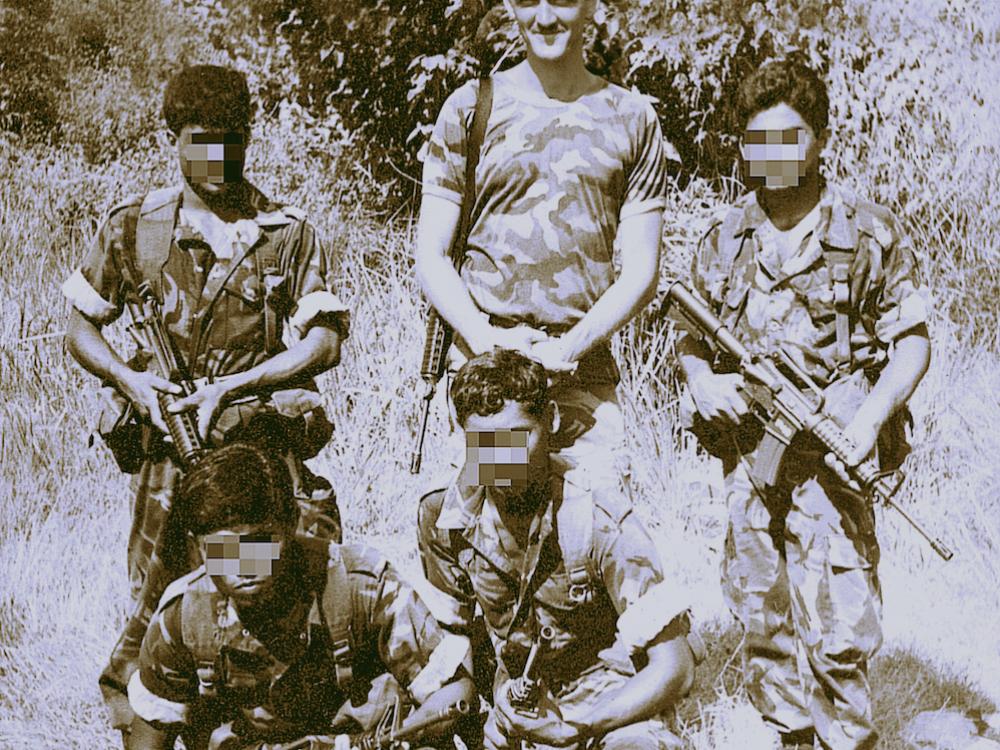

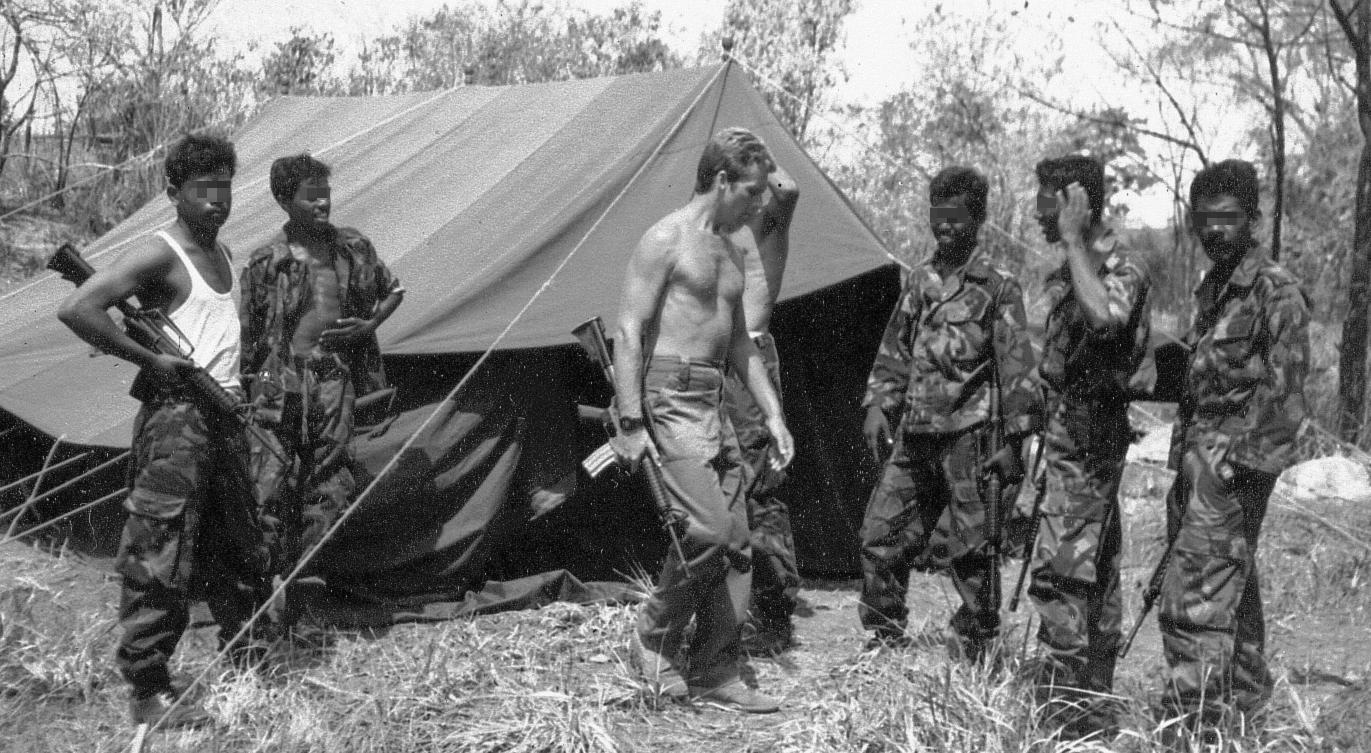

The controversy has shed new light on Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), one of Britain’s first private military companies, and its role in Sri Lanka. KMS was staffed by ex-Special Air Service personnel and in the 1980s was contracted to assist the Sri Lankan government’s counter-insurgency against the Tamil independence movement. The mercenaries trained Sri Lankan soldiers and even took part in operations, having provided a pilot for a helicopter gunships that massacred Tamil civilians. KMS operatives effectively fought in Sri Lanka’s war, even as the UK government downplayed its official involvement.

At the time, Sri Lanka’s campaign was drawing international criticism for human rights abuses. The declassified British documents show that Prime Minister Thatcher was keenly aware of Britain’s military support to Colombo. In fact, officials had briefed Thatcher on the assistance already being given – including KMS training programmes and arms exports being handled “flexibly” to benefit Sri Lanka. Far from being a rogue operation outside government knowledge, KMS’s work was discussed at the highest levels in Downing Street.

Remarkably, the 1985 files indicate that Thatcher wanted to step up British aid to Sri Lanka’s counter-insurgency efforts. Her top foreign policy adviser, Charles Powell, wrote in one newly disclosed document that “Her view is that it is not enough.”

This note conveyed Thatcher’s dissatisfaction with the current level of UK support – which already included the covert KMS deployment – and her desire to do more. In response, Britain’s Chief of the Defence Staff proposed identifying additional British experts who could be sent to assist Sri Lanka. One suggestion was retired Major General Corran Purdon, of private firm Falconstar (described in the files as “a rival firm to KMS”). If Purdon proved unsuitable, the Ministry of Defence “could easily come up with a variety of other names”, the defence chief assured, underscoring London’s willingness to offer further personnel.

Thatcher ultimately held off on any immediate new deployment – apparently calculating that any overt boost in military support should wait until India (which sympathised with the Tamil cause) had finalized the purchase of British-built Westland helicopters. However, the Prime Minister raised no objection to KMS continuing its operations in Sri Lanka, effectively green-lighting the mercenaries to carry on their work. These revelations cast fresh doubt on long-standing British government claims, including statements to a later United Nations inquiry, that London “had no locus to intervene in what was a commercial contract” between KMS and Sri Lanka’s government. On the contrary, the declassified files show the Thatcher administration not only knew about KMS’s contract but was actively considering expanding Britain’s involvement in Sri Lanka’s war.

The Foreign Office’s delay in releasing the KMS files has had tangible consequences. By keeping the documents under wraps for years, the FCDO may have impeded accountability efforts related to war crimes. The disclosed papers contain evidence of atrocities that was not proactively shared with investigators. In one document, a KMS director reported that Sri Lankan security forces had carried out a “wholesale massacre of women and children”. Yet Hand admitted during the tribunal that the Foreign Office never alerted the police to such incriminating material in its archives. Despite reviewing these files years earlier, officials chose not to flag potential evidence of historical crimes to law enforcement. Hand – who once headed the FCDO’s human rights department – defended this decision, suggesting his team saw nothing that in their view merited referral to police.

Meanwhile, an investigation by the Metropolitan Police into alleged war crimes by KMS personnel has been ongoing since 2020. That probe was prompted by the publication of a book on KMS by investigative journalist Phil Miller, which brought fresh attention to the mercenaries’ activities in Sri Lanka. Detectives from the Met’s War Crimes Team began examining whether any Britons could be liable for crimes committed during the 1980s conflict. However, the delayed release of official documents meant that crucial leads emerged late. Notably, one prime suspect – Major Brian Baty, a former SAS officer who led KMS operations on the ground in Sri Lanka – died in February 2020 just as the investigation was starting. Baty’s death, which came one month after the KMS exposé was published, denied investigators the opportunity to question him.

Read more from Declassified UK here.