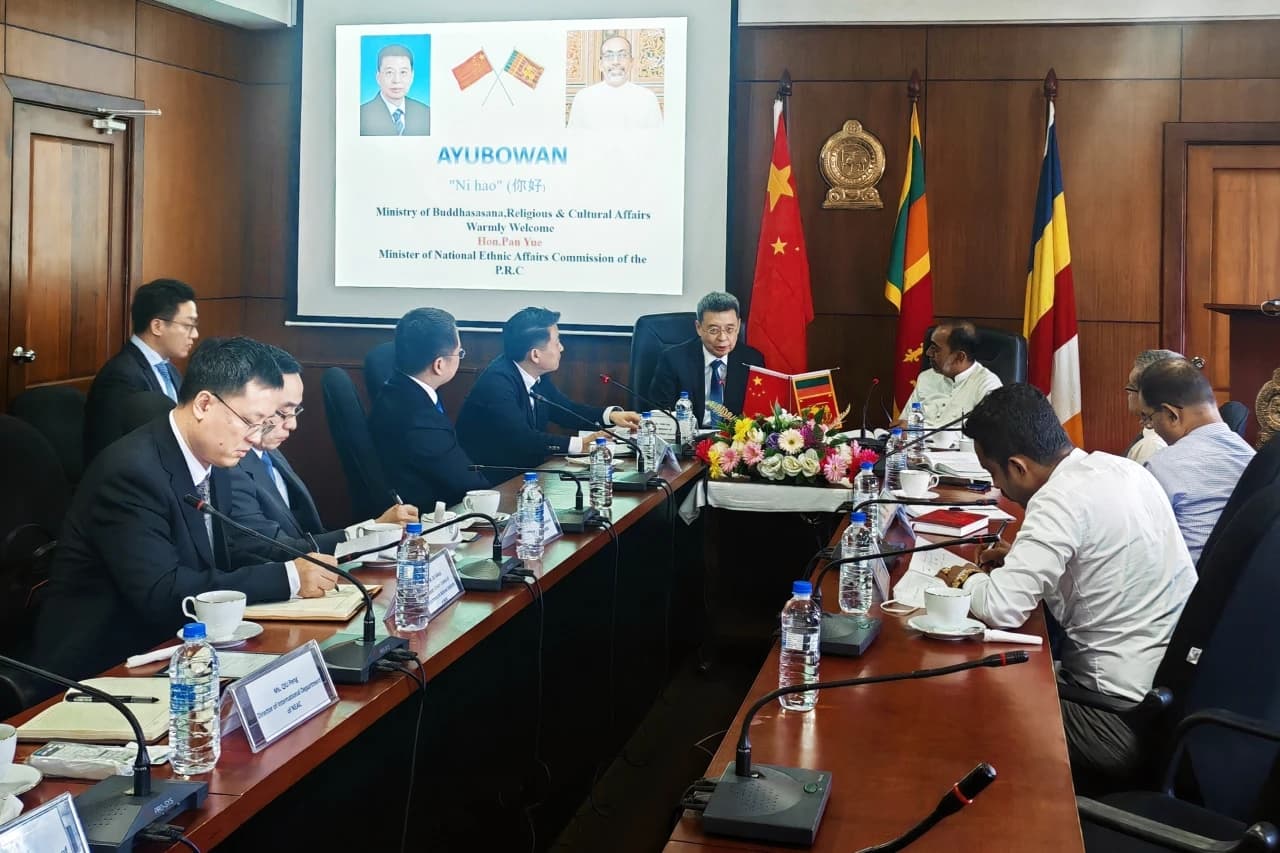

China’s Minister of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, Pan Yue, led a high-profile delegation to Colombo last month, where he discussed ‘ethnic harmony’ and ‘reconciliation efforts’ with Sri Lankan officials.

The visit has raised questions about China’s deeper engagement in Sri Lanka, particularly in the Tamil homeland of the North-East. Given China’s 'Regional Ethnic Autonomy System', its own track record on ‘ethnic affairs’ domestically, Beijing's strategic interests in Sri Lanka, and growing global influence, Pan Yue’s visit may signal more than just routine diplomacy.

Notably, however, the Chinese minister did not meet with any Tamils from the North-East during his visit. Instead, he met with government officials, including from the controversial Ministry of Buddha Sasana, as the Sri Lankan state continues its intense Sinhalisation of the Tamil North-East.

Who is Pan Yue?

Pan Yue is a long-standing Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official and the current head of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission (NEAC)—the state body responsible for managing China’s policies on ethnic minorities. His role places him at the centre of Beijing’s approach towards ‘ethnic harmony’ in regions like Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia.

Under Pan’s leadership, China has been implementing the Regional Ethnic Autonomy System, a policy framework that ostensibly grants these various regions a degree of self-rule.

China’s influence in Sri Lanka

Dissanayake meets Jinping.

Pan Yue’s visit is part of China’s broader engagement in Sri Lanka, particularly in the wake of Sri Lanka’s deepening economic ties with Beijing. It comes just weeks after Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s state visit to China, where he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted and signed 15 Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) covering economic development, education, media, and culture.

China’s interests, however, are not limited to Colombo. In recent years and months, there have been visits by Chinese officials to the Tamil homeland of the North-East. Earlier this year, the Chinese ambassador to Sri Lanka, Qi Zhenhong, visited Jaffna, Mullaitivu, Kilinochchi, and Mannar, distributing aid and making public statements about Tamil political aspirations.

However, when directly questioned about China’s role in Sri Lanka’s war against the Tamil people, Qi evaded the topic, instead emphasising China’s satisfaction with the election of the National People's Power (NPP) in Jaffna.

What does Pan Yue’s Visit Mean for the Tamil Nation?

Monks marching in Jaffna earlier this month.

For decades, Sri Lanka has pursued a Sinhalisation policy in the North-East, displacing Tamils, militarising Tamil lands, and suppressing Tamil political aspirations. It continues to occupy the North-East and the current government has stood steadfast against devolving powers to the region.

Even legislation that has supposedly been adopted into the Sri Lankan constitution, such as the 13th Amendment which Tamils themselves have long rejected, remains unfulfilled.

China's Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law, first introduced in 1984, allows minority regions like Tibet and Xinjiang to have their own autonomous governments, with local control over cultural, educational, and economic matters—at least in theory. However, in practice, Beijing retains tight centralised control, and these regions have faced heavy political repression, forced assimilation, and crackdowns on dissent.

China’s ethnic model presents an alternative to outright assimilationist Sinhala nationalism, as it claims to acknowledge ethnic differences and regional governance. If implemented genuinely, it could, at least in theory, allow Tamils in the North-East to have greater control over their lands, resources, and governance, as well as official recognition of Tamil language and cultural identity.

However, the reality of China’s model offers a cautionary tale.

In Tibet and Xinjiang, Beijing maintains strict oversight through heavy securitisation, population control measures, and political repression. Several human rights organisations and governments cross the world have accused China of committing a genocide, and reports of rights abuses are rife.

If Sri Lanka adopts a superficial version of this system, it may simply result in ongoing military occupation and curbs on Tamil political aspirations, enforced through surveillance and repression.

Indeed, given how Pan Yue did not meet with any Eelam Tamils during his visit and instead chose to meet with government officials, many will be fearful of what is to come.

Tamil National People’s Front (TNPF) parliamentarian Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam recently raised the visit in parliament, noting how China’s treatment of Uighurs is accused of being genocidal and how there is a policy of “ending minority culture” from Beijing.

China's head of Ethnic Affairs is keen to end minority culture. That is their policy in #China. The same sort of sentiments were expressed by @GotabayaR. When the Chinese Ambassador soon after the elections goes to Jafffna & made these comments, and when a Minister whose ministry… pic.twitter.com/F1CLok26TR

— Manthri.LK_Watch (@ManthriLK_Watch) March 17, 2025

“Why on earth would a Chinese minority related ministry come to Sri Lanka and not meet any of the minorities? And only meets the Buddha Sasana ministry?,” he questioned.

“The Buddha Sasana ministry, especially the archaeological department is something that is extremely controversial. We have been accusing the archaeological department specifically of systematically carrying out cultural genocide in the North-East.”

China’s role in the Tamil question

China’s engagement with Sri Lanka has historically been driven by economic and military interests, not ethnic reconciliation. Beijing armed the Sri Lankan state during the war, providing critical military aid that helped Colombo defeat the LTTE in 2009, with a genocide that killed tens of thousands of Tamils. Beijing also blocked UN resolutions calling for accountability and provided weapons, diplomatic cover, and economic aid to the Rajapaksa government.

It has since become Sri Lanka’s largest creditor, backing controversial infrastructure projects like Hambantota Port and Colombo Port City.

Chinese officials distributing relief to Tamils.

Yet, China has also expanded its presence in the Tamil homeland. In recent months, Chinese officials have distributed aid in flood-hit Tamil regions, engaged in public diplomacy efforts in Jaffna and Mannar and sought to position themselves as an alternative to Indian influence in the North-East. Ponnambalam noted how China wanted to open a new ‘cultural affairs’ centre in Jaffna too.

Could Pan Yue’s visit signal an expansion of China’s involvement in the Tamil issue? If Beijing pushes for a reconciliation model based on its own ethnic policies, would it simply serve as another tool for Colombo to retain centralised control over Tamil areas?

The visit also comes as China has increasingly sought to expand its global role in conflict resolution, having brokered an agreement between several Palestinian factions last year.

If China were to seriously engage with the Tamil question, it would require a fundamental shift in its policy—one that acknowledges Tamil grievances, demands for accountability, and the need for genuine political autonomy.

While Beijing may believe its model of ethnic autonomy may appear a viable alternative compared to outright Sinhala-Buddhist dominance, it does not guarantee real self-determination or protection from state repression. If Sri Lanka does take inspiration from China’s ethnic governance approach, it is likely to be tightly controlled, heavily militarised, and politically restricted, mirroring what has happened in China’s so-called autonomous regions.

If Beijing is looking to present itself as a neutral actor and regional influence on the island, it cannot ignore Tamil aspirations.